Why Do Birds Migrate, and When? What To Know About Bird Migration

Photo by Manu Nair/Adobe Stock

In human life, travel is a hassle. Sure, you’d love to take a vacation, but when? Where? And what should you pack?

Birds would balk at all the hullabaloo. When they migrate, they already know when it’s time to leave and where to go—no suitcase required.

The magical thing about bird migration (aside from the fascinating science behind it—more on that in a minute) is that a whole crew of charming birds might choose to make a pit stop at your home.

Key Takeaways

- Bird migration is the seasonal movement of birds between breeding and wintering grounds.

- Birds migrate to survive, sometimes traveling long distances to find warmer climates, safer nesting areas, and abundant food sources.

- Migration patterns vary by species—some birds travel thousands of miles, while others don't migrate at all.

Why Do Birds Migrate?

Of course, birds don’t migrate just to say hello and sightsee in your backyard. They tend to travel to find temperate weather, a safe place to have their babies, and, of course, lots of food.

“Even though migration is really difficult for many species and very dangerous overall, they’re able to raise more chicks, just because they have those abundant resources that they wouldn’t have if they didn’t migrate,” says Aimee M. Van Tatenhove, Ph.D., an ornithologist and postdoctoral fellow at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York.

The longest bird migration, for example, is the Arctic tern, who probably wouldn’t travel 50,000 miles round-trip each year if not for a good reason.

When Do Birds Migrate?

Photo by Chewy

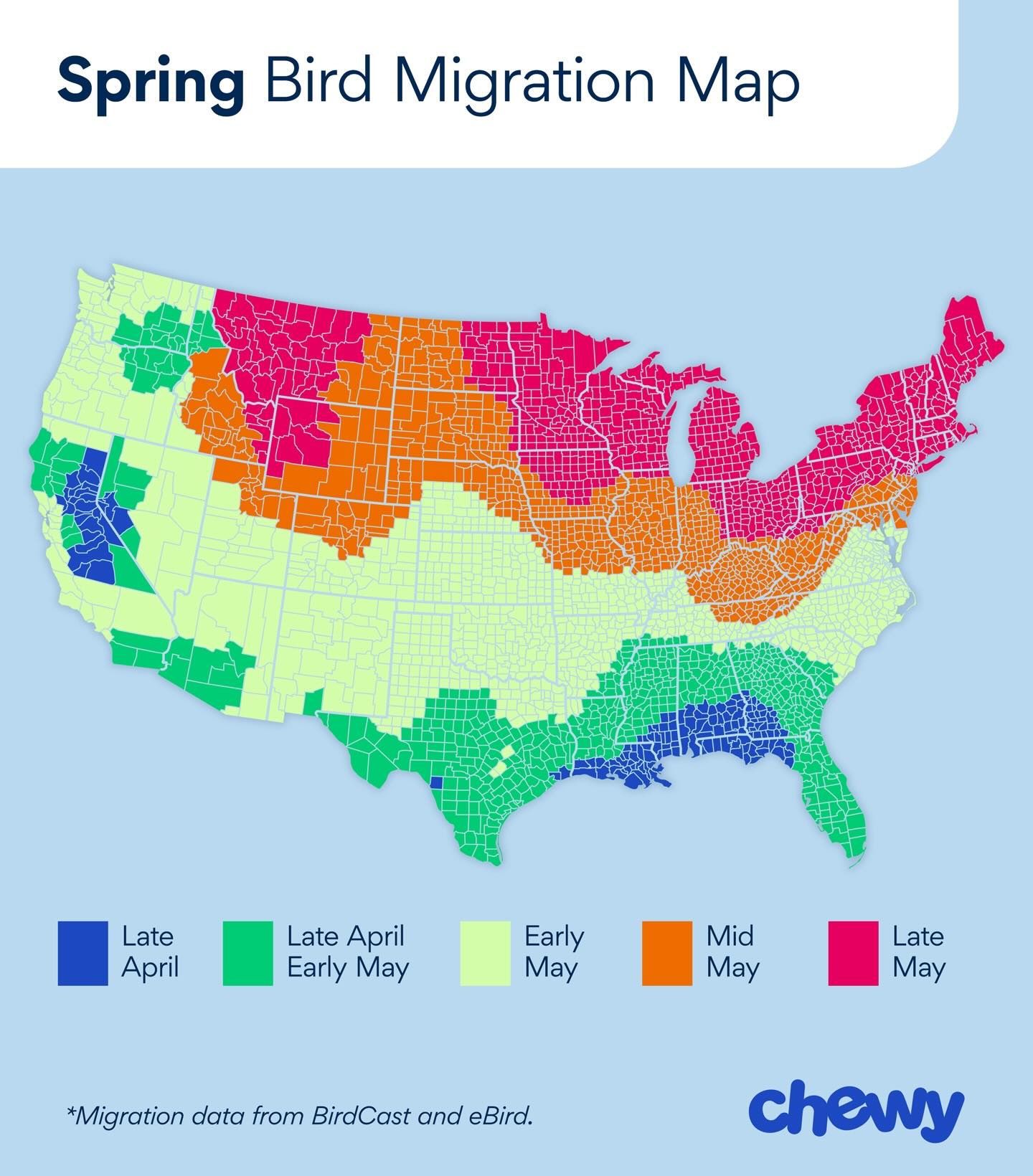

There are two bird migration seasons: spring and fall.

“It’s usually end of April to May for spring, and then September to early October for fall,” says Jordan E. Rutter, M.Sc., an ornithologist and the director of communications at the American Bird Conservancy in Washington, D.C. “Those are when you really get these massive movements of birds through the country. I’m talking billions of individuals … all across the country.”

So, how does a bird know that it’s time to hit the road?

“A lot of birds like to use good wind conditions to help them start their migration journey,” Van Tatenhove says. “Some of the hawk species or hummingbirds, or even pelicans, use that cue.”

Birds also notice changes in the light as seasons change, just like humans.

“That’s one of the coolest things,” says Rutter. “A lot of birds are photoperiod-dependent. They really tune into the timing of the sun. So, when the days are getting shorter, they know to get ready, and when the days are getting longer, they know. Their entire hormone system is really tied to the sun, and that’s because it’s so reliable.”

Rutter describes this period of changing light as the “spark” that ignites the desire to migrate, but then everything else must fall into place. The bird will also notice food sources drying up and temperatures beginning to shift. “And it’s like, ‘OK, now I really can’t stay here anymore.’”

Do All Birds Migrate?

However, not all birds migrate—and some are just downright homebodies. In fact, there are lots of species you can see year-round, no matter where you live.

“A lot of them have physiological capabilities to just deal with the cold,” Van Tatenhove says. “Especially in the southern United States, there are some birds that, because it is warmer, they’re able to stay there.”

It depends on the exact species, but some juncos, sparrows, chickadees, cardinals, and woodpeckers don’t migrate.

Popular migratory species, on the other hand, include many orioles, bluebirds, finches, yellow warblers, and snow geese—but again, there are exceptions.

And, to add extra nuance, even birds of the same species can be migratory … and non-migratory. For example, in winter, you may see a migratory American goldfinch in the West or Southwest; but other American goldfinches choose not to migrate and live year-round in the Midwest and Northeast.

What Migrating Birds Will I See?

Migratory birds seen during the summer in the U.S. have flown north from warmer places—like Mexico, the Caribbean, Central and South America, and even just Florida—to find more abundant food sources in a temperate northern climate.

Migratory birds seen during the winter throughout the U.S. have flown south from colder areas—like Alaska, Canada, the Arctic, or even just Midwestern and Northeastern states—to find food sources that are unavailable in the cold and frost.

Here’s a breakdown of some popular birds you’ll see in each season (as well as year-round), but this is only a sampling. (After all, more than 450 species of migratory birds travel throughout the U.S. and Canada each year.)

If you’re hoping to see when your favorite bird might be out and about, the Cornell Lab is an easy place to search.

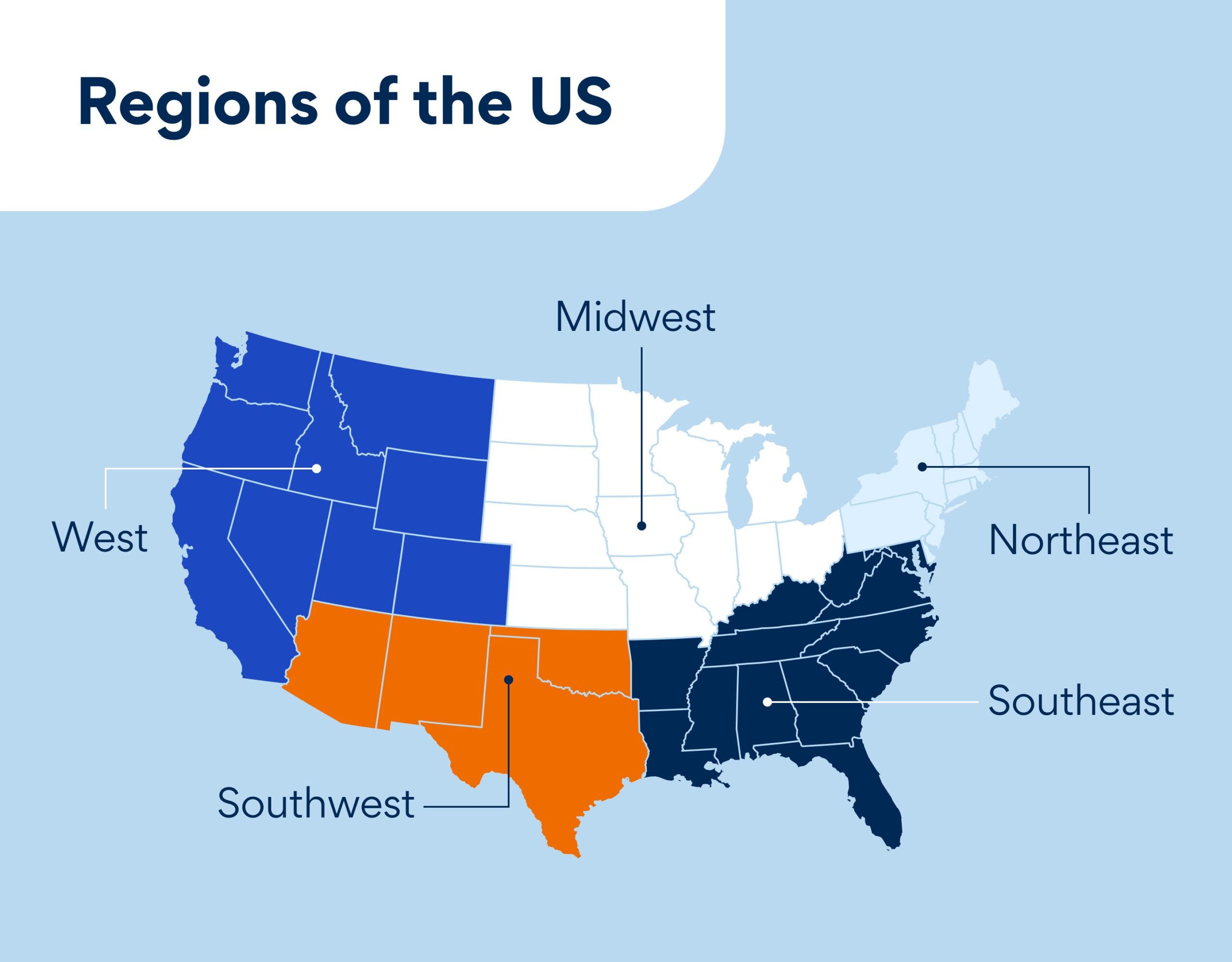

Northeast

Baltimore orioles, Eastern bluebirds, and ruby-throated hummingbirds are some of the most popular birds that migrate in the summer. In the winter, you’ll see the snow bunting and the Lapland longspur.

In the summer, you’ll see these migratory birds in the Northeast:

- Baltimore oriole

- Eastern bluebird

- Indigo bunting

- Ruby-throated hummingbird

- Scarlet tanager

- Wood thrush

- Yellow-billed cuckoo

- Yellow-rumped warbler

- Yellow warbler

In the winter, you’ll see these migratory birds in the Northeast:

Southeast

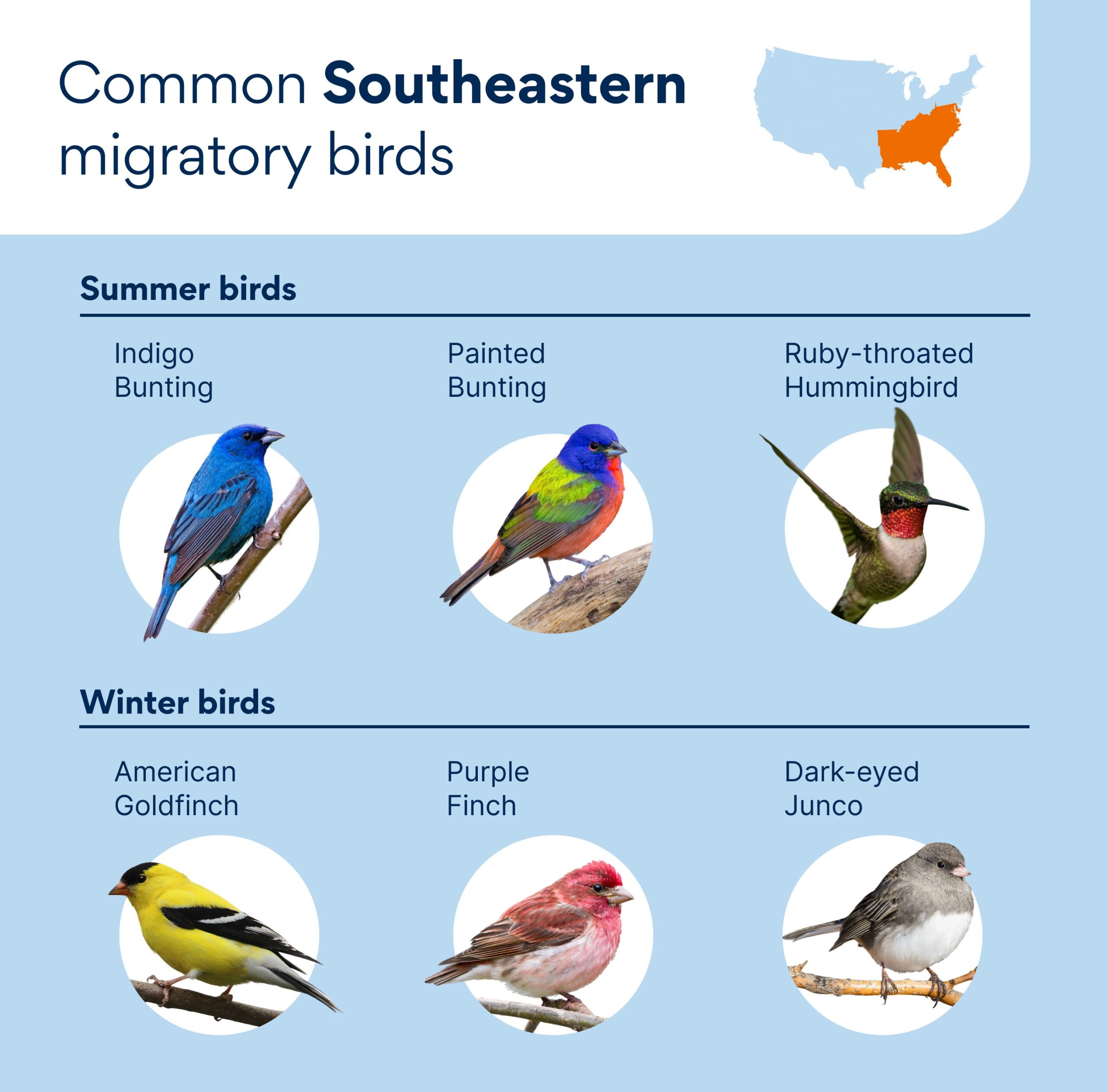

Some of the most popular migratory birds are the painted bunting (a type of finch) and the ruby-throated hummingbird in the summer, and the American goldfinch and the purple finch in the winter.

In the summer, you’ll see these migratory birds in the southeast:

- Indigo bunting

- Mississippi kite

- Painted bunting

- Prothonotary warbler

- Ruby-throated hummingbird

- Wood thrush

- Yellow-billed cuckoo

In the winter, you’ll see these migratory birds in the southeast:

Midwest

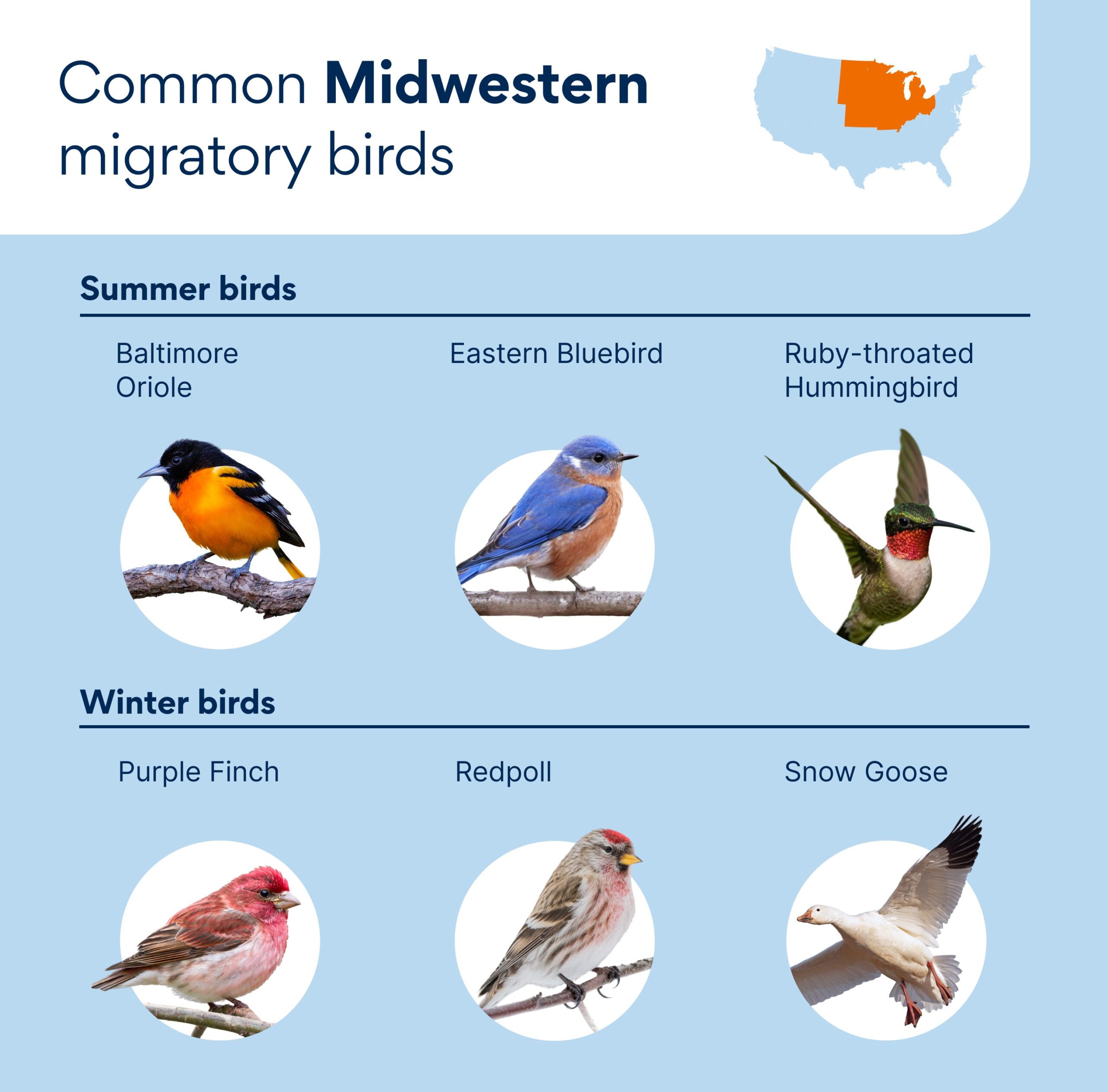

Baltimore orioles, Eastern bluebirds, and ruby-throated hummingbirds are some of the most popular migrating birds you’ll see in Midwest summers. During the winter migration, the purple finch and snow goose are common.

In the summer, you’ll see these migratory birds in the Midwest:

- Baltimore oriole

- Bobolink

- Dickcissel

- Eastern bluebird

- Indigo bunting

- Ruby-throated hummingbird

- Scarlet tanager

- Wood thrush

- Yellow-billed cuckoo

- Yellow warbler

In the winter, you’ll see these migratory birds in the Midwest:

Southwest

Some of the most popular southwest migratory birds are the black-chinned hummingbird and the Bullock’s oriole in the summer. The American goldfinch as well as the dark-eyed junco (one of the most common birds in North America) migrate through in winter.

In the summer, you’ll see these migratory birds in the southwest:

- Black-chinned hummingbird

- Bullock’s oriole

- Hooded oriole

- Indigo bunting

- Painted bunting

- Phainopepla

- Yellow warbler

- Western tanager

In the winter, you’ll see these migratory birds in the Southwest:

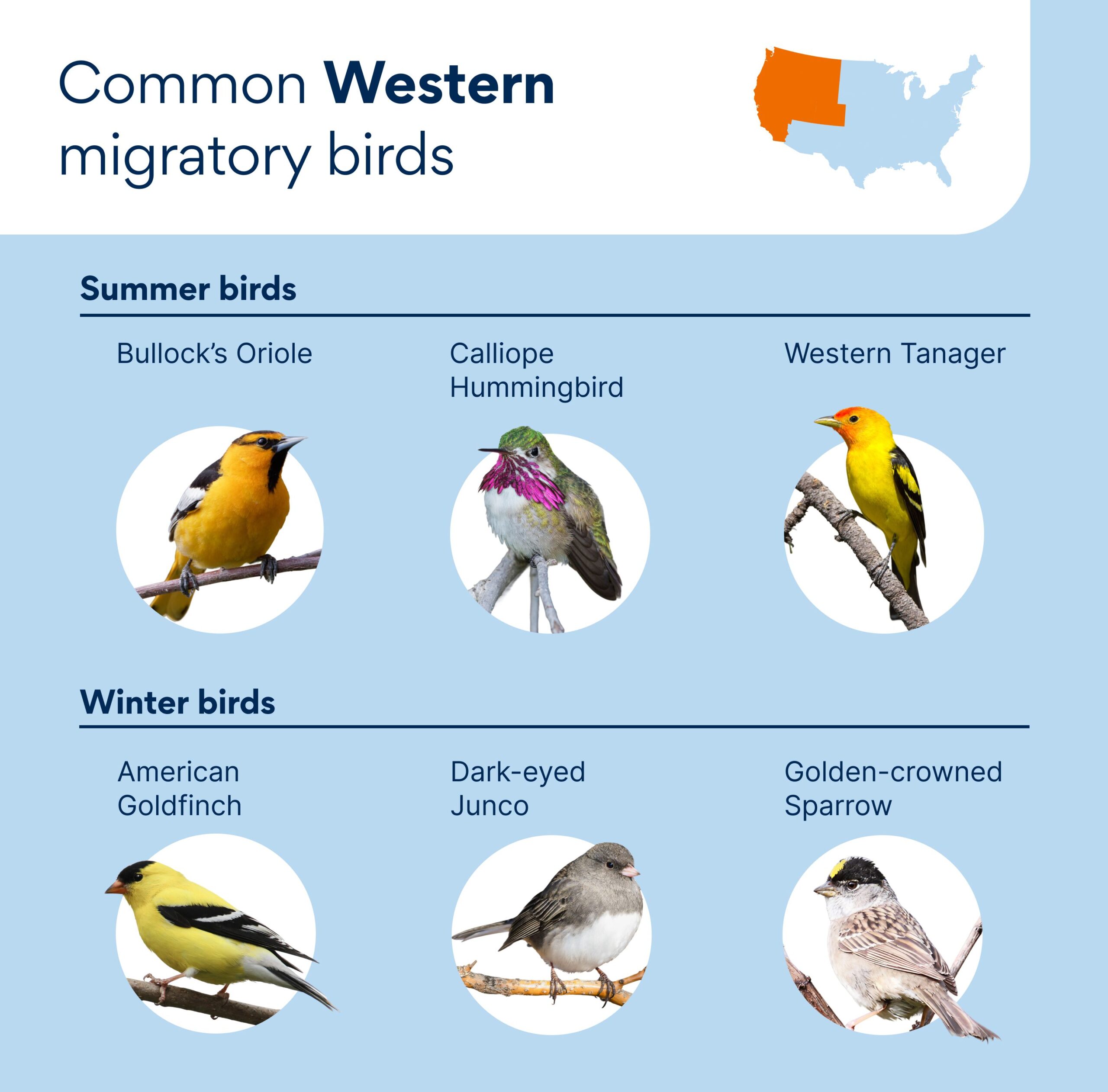

West

Stretching from the Pacific Northwest down to Southern California, there are many different birds migrating throughout the West. Some of the most popular migratory birds are the Bullock’s oriole and Calliope hummingbird in the summer, and the American goldfinch as well as the dark-eyed junco in winter.

In the summer, you’ll see these migratory birds in the West:

- Black-chinned hummingbird

- Bullock’s oriole

- Calliope hummingbird

- Lazuli bunting

- Mountain bluebird

- Western tanager

- Yellow warbler

In the winter, you’ll see these migratory birds in the West:

How To Attract Migrating Birds

If you’d like to welcome these species into your backyard, set up a bird feeder. However, not just any food will do—it depends on the type of bird you want to attract.

Recommended Products

“You can’t provide the same thing for a woodpecker and a cardinal, and expect them to both come,” Rutter says. “You have to customize it.”

Here are some tips for attracting your favorite birds:

- Bird seed: For most birds, you can buy a specific bird seed tailored to that species. It should say on the packaging which species it will attract.

Recommended Product

- Sunflower seeds: Put out a feeder with sunflower seeds, and you’re likely to attract cardinals year-round. Finches and sparrows may visit during migratory seasons (and house finches will stop by all year).

Recommended Product

- Suet: Suet will be a hit with woodpeckers; many will visit year-round.

Recommended Product

- Nectar: You can buy a special feeder and nectar to attract various hummingbirds passing through your area.

Recommended Products

- Thistle and nyjer: Thistle and nyjer are favorites with American goldfinches, who are both year-round and migratory, depending on where you live.

Recommended Product

- Millet: In the Southeast and Southwest, you can attract bright-green and rainbow-colored painted buntings by setting out some millet.

- Jelly and oranges: Orioles have a sweet tooth, so it’s OK to get a little creative if you’re looking to bring some to your back yard. But stick to jelly and oranges, Van Tatenhove says.

Never put out human food—it does more harm than good. (Citrus, jellies, and jams for the orioles are an exception.) Refresh the seed regularly, since birds may start to depend on you for a nice snack. Regularly clean the feeder, too.

Bird baths are also good additions to your yard, especially in drier states like New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah, Van Tatenhove says.

If you want to see migrating birds, don’t wait until the last minute. Put the feeder out in March or April for summer, and August or September for fall.

Keeping it out year-round is even better—resident birds will already be there, signaling to migrating birds that it’s a great place to stop and refuel. Suet is a great choice for cold-weather bird feed.

With any luck, you’ll have a cheerful little crew of happy birds stopping by—and, to boot, you’re doing a good deed, helping make an exhausting journey a bit easier for some feathered travelers.