Meet the Bluebird, and Learn How To Help Them Thrive

Photo by mlharing/E+

Few birds capture our attention quite like bluebirds. With their bright blue feathers and cheerful songs, these little birds are symbols of joy and hope.

But beyond their beauty, bluebirds also have a fascinating conservation success story. Learning how to support their habitat needs and supplement their favorite food sources can help you become a part of their rebound, too.

Find out how to attract bluebirds to your area, including unique nesting habitat needs and food they’ll love to eat.

Key Takeaways

- Bluebirds are a conservation success story, rebounding from a steep population decline in the mid-20th century.

- There are three types of bluebirds in North America: the Eastern bluebird, the Mountain bluebird, and the Western bluebird.

- To attract bluebirds, create open, pesticide-free spaces with native fruiting plants and nesting boxes.

What Is a Bluebird?

Bluebirds belong to the thrush family and are known for their brilliant blue plumage, rusty or white underbellies, and melodic calls.

David Mizejewski, a naturalist with the National Wildlife Federation, explains that bluebirds are unique among North American songbirds because you don’t see their color very often in nature. “Aside from blue jays or indigo buntings, there aren’t many non-tropical birds that share that vibrant shade of blue,” he adds.

Additionally, Mizejewski says that, like most other bird species, male bluebirds are generally brighter in color. Female bluebirds are more subdued, with dusky gray-blue feathers.

Types of Bluebirds

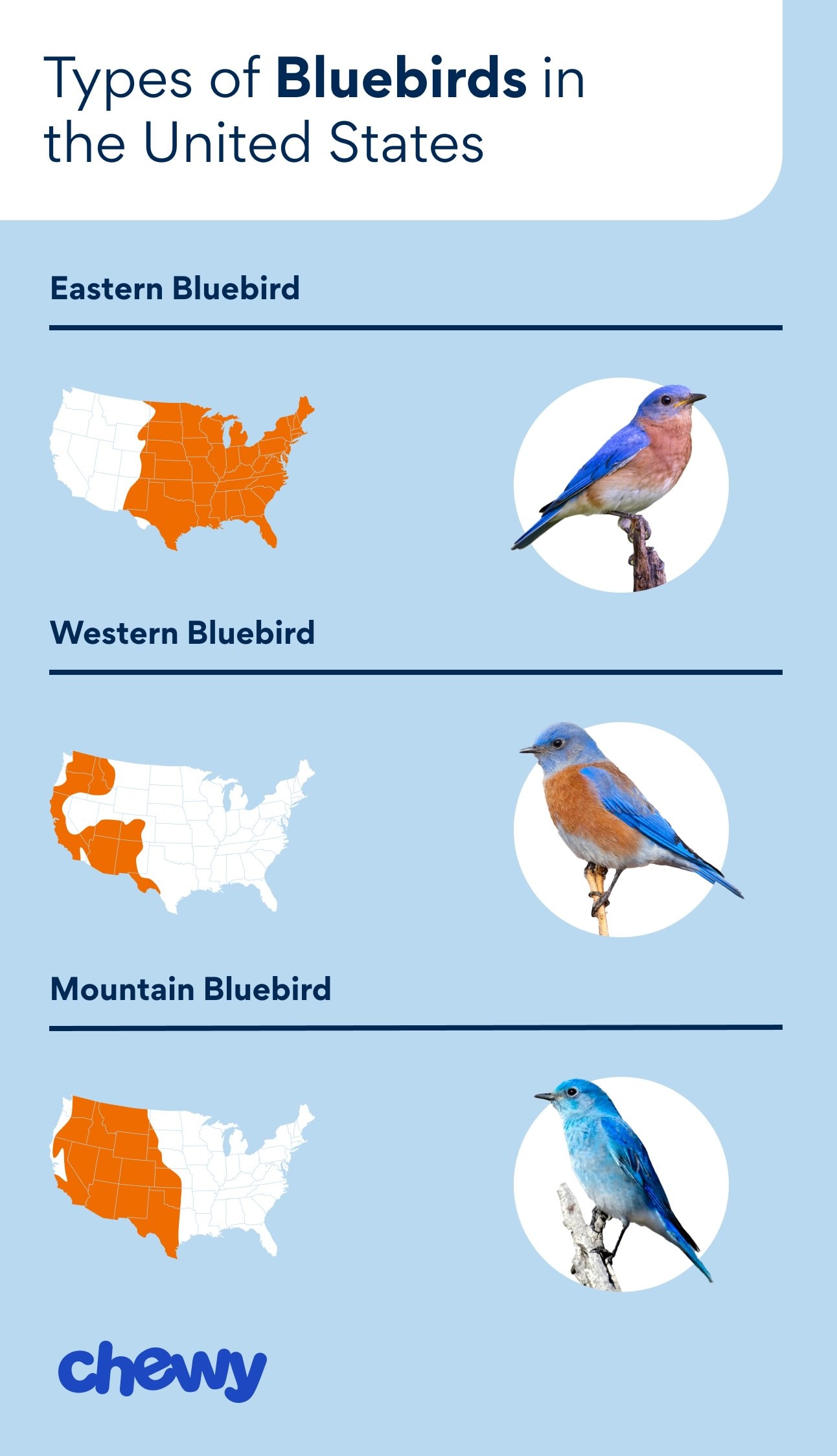

Photo by Chewy

Three bluebird species can be found across North America:

- Eastern bluebird: Found east of the Rockies, males sport a bright blue back with a rusty-red chest and throat. Females have orange-brown bodies with a white belly and blue tinges on their wings and tail, which resemble blue highlights against their neutral body coloring.

- Western bluebird: Similar to the Eastern, but males have deeper blue plumage that extends to their throat, and rust coloring on their chest extends across the back. Females are not as brightly colored as males, with chestnut brown bodies and gray-blue on their wings and tails.

- Mountain bluebird: No rust coloring on these fellas! Males are a striking sky-blue from head to wing. Females are a dusty gray-brown, with more subdued pale gray-blue tones on their wings and tail.

Where Do Bluebirds Live?

Eastern bluebirds are found across the eastern U.S. and into southern Canada, while Western bluebirds range through the western states into Mexico. The Rockies act as a rough dividing line between Eastern and Western species.

Though the range of Mountain bluebirds can overlap with Western bluebirds, the former prefers higher elevations of alpine meadows and clearings.

All bluebirds prefer open spaces, meadows, pastures, and woodland edges. They are less likely to appear in heavily urban or densely wooded areas.

“If you live in rural or semi-rural suburbia, you’re more likely to see them,” Mizejewski says. “These aren’t deep-forest birds.”

Bluebird Habitats and Nesting Requirements

All three types of bluebirds prefer similar real estate when building a home to raise their young.

Known as “secondary cavity nesters,” they rely on holes and cavities created by other species, like woodpeckers. They seek out holes in trees along meadow edges where there’s easy access to nearby insect-rich fields and grasslands.

That dependence has historically made them vulnerable to competition from aggressive invasive species like European starlings and house sparrows, which often take over available nesting sites.

As humans cleared dead trees and stumps for farmland and suburbs, bluebirds had even fewer nesting sites to choose from. Add in harsh weather and heavy pesticide use in the 1940s–1950s, and Eastern bluebird numbers are thought to have dropped by as much as 90%.

Bluebird Nesting Boxes and the Bluebird Trail

Thankfully, community conservation efforts helped turn things around.

“Starting in the 1960s, people began putting out nesting boxes for bluebirds, and this whole bluebird trail movement really helped them bounce back,” Mizejewski explains. “Today, all three species are listed as [of] least concern, and Eastern bluebird populations have actually been growing.”

It’s a rare bit of good wildlife news, largely thanks to people caring enough to help. And while bluebird populations are currently stable, that doesn’t mean that there’s no risk to them at all.

“Birds around the U.S. are in danger of a decline due to a variety of factors, including window strikes, habitat loss, and widespread pesticide use affecting food sources,” says Maria Kincaid, head ornithologist with FeatherSnap.

Kincaid and Mizejewski have several tips for backyard birders to help restore bluebird habitat and food sources, including:

- Avoiding pesticides. “Insects are an important part of the ecosystem and are a food source for many birds and other animals,” Kincaid says.

- Planting native plants that produce fruit and attract insects. Kincaid says prioritizing fruit plants helps not only bluebirds, but many species of birds (especially during cold months).

- Install safe, well-placed nesting boxes. Mizejewski recommends checking the NABS-approved guidelines when building or setting up bluebird nest boxes.

- Keep cats indoors. Outdoor cats are responsible for killing 2.4 billion birds every year in the U.S. alone, according to the American Bird Conservancy. So instead of letting your cat out unsupervised, keep them inside a catio or on a leash and harness—these restrictions are also for their own safety.

Do Bluebirds Migrate?

Bluebird migration varies depending on the species and their specific region.

Many Eastern bluebirds will migrate short distances southward in winter, though some remain year-round if food is available.

Mountain and Western bluebirds are also known to shift their ranges in response to weather and insect availability. In general, Mizejewski says they’ll spend their summers breeding in open habitats and move to lower elevations or warmer areas in winter, where they’re able to find bugs and berries to snack on.

What Do Bluebirds Eat?

Bluebirds are mainly insect eaters.

“Bluebirds feed their young mainly caterpillars, other insects, and spiders,” says Charlie Roberto, Teatown Lake Reservation’s resident “birdman” and founder of Teatown’s annual Eaglefest in New York’s Hudson Valley. “Later in the season, they’ll eat berries and fruit.”

In warmer months, bluebirds usually forage on the ground for bugs or in tree branches. In winter, insects disappear and fruit becomes essential. Bluebirds especially rely on native plants like sumac, juniper, holly, dogwood, hackberry, elderberry, raspberries, and blueberries.

If you live in an area where bluebirds are common, you may have luck enticing bluebirds to your feeder with seeds and mealworms.

Recommended Products

In the winter, when insects aren’t plentiful, you can set up a suet feeder to attract bluebirds.

Recommended Product

How To Attract Bluebirds

Attracting bluebirds means creating the right conditions in your yard, as well as living in the right area.

“If you’re in a heavily wooded area, they probably won’t come. [The] same goes for suburbia or cities,” Mizejewski says. “They’ll show up in rural places with open spaces and meadows.”

Plant Native Plants

Countryside is key—and so are food sources. Mizejewski and Roberto both recommend planting shrubs native to your region to ensure bluebirds have access to suitable food sources during the winter months.

“Plants like sumac, holly, juniper, native raspberries, and blueberries will provide fruits they can eat in the colder months of December and January once the bugs they need die off,” Mizejewski says.

Find which fruit-bearing shrubs are native to your area at Garden for Wildlife. Other wildlife, including songbirds such as robins and cardinals, as well as pollinators like hummingbirds, butterflies, and bees, will also appreciate these native food sources.

Avoid Pesticides

Skip the insecticides. Even ones labeled eco-friendly can harm bluebirds and other winged friends.

“Pesticides are one of the major dangers they face,” Roberto says. Once an insecticide is sprayed in a yard, garden, or field, bluebirds will then catch the dying insects and feed them to their babies.

Provide Nest Boxes

Create spaces bluebirds can use to raise their young, but keep in mind that not just any old birdhouse will do. In fact, unmonitored or improperly built nesting boxes can do more harm than good.

“Bluebirds will readily use nest boxes, but it’s important to do it right,” Mizejewski says. Make sure your nesting box follows these specifications:

- According to the North American Bluebird Society nesting box specifications, a round entry hole that’s 1-9/16 inches wide is acceptable for all three species of bluebirds. Oval openings or a horizontal slot may also be used. However, entrance sizes differ slightly depending on the region, but all are designed to keep out the larger European Starling.

- Include drainage holes in the floor and ventilation under the roofline.

- Ensure there’s a roof overhang to help keep wind and rain out of the entrance.

- Avoid adding a perch. Mizejewski says it’s unnecessary and can aid predators.

- Mount boxes 4–6 feet high on a pole. Use a nesting box with a predator guard to keep out snakes and raccoons. Add a wobbling baffle to the pole to help keep climbing critters out of the nestbox, too.

Recommended Products

Offer Mealworms

While they’re not regular feeder visitors, some backyard birders have luck attracting bluebirds with a specialized mealworm feeder that contains live or dried mealworms.

“While bluebirds aren’t the most frequent feeder visitors, they will show up—especially in early spring, late fall, and winter,” Kincaid says. “Offering mealworms, sunflower seeds, or dried fruit can bring them in, particularly with a dual-bin feeder that allows a mix of foods.”

Recommended Product

Discourage Competitors

House sparrows and starlings are aggressive invasive species that often outcompete bluebirds for nest sites. That’s why monitoring nest boxes is so critical.

Volunteers like Roberto have been monitoring bluebird nesting boxes since the “bluebird trails” movement was started. He emphasizes the value of providing safe spaces where bluebirds can raise their young.

“Putting nest boxes out in a pesticide-free lawn and adding predator guards have helped restore bluebirds to our region,” he adds.

Provide a Fresh Water Source

All wildlife—including bluebirds—requires fresh water and will appreciate a spot for drinking and bathing. Adding a bird bath or small water feature to your landscape will only increase your chances of spotting a feathered visitor.

Recommended Product

Bluebirds are more than just beautiful backyard visitors. They’re also a conservation success story that demonstrates how human efforts can have a profoundly positive impact on wildlife.

By including the right plants, nest boxes, food sources, and safe habitats in your own space, you can help ensure these brilliant songbirds thrive for generations to come.

FAQs About Bluebirds

How long do bluebirds live?

In the wild, most bluebirds will live 6–10 years, though many don’t survive their first year. Habitat loss, pesticide use, competition from more aggressive species, and predation by cats, snakes, and raccoons can threaten their survival.

What does it mean if you see a bluebird?

Bluebirds are often regarded as symbols of happiness, renewal, and hope. Kincaid says bluebirds are also often seen as symbols of joy and luck. “In some Native American cultures, they represent spring, wind, weather, and the sun,” she says.

Where do bluebirds build nests?

Bluebirds are known as cavity nesters, meaning they build their homes in holes and artificial nesting boxes. They’ll use natural tree holes or hollow fence posts, which are found in nature, or nest boxes placed in open habitats.

Do bluebirds mate for life?

“All three species are socially monogamous, but they don’t mate for life,” Kincaid says. “Pair bonds usually last a breeding season, though sometimes longer.”

Some Eastern bluebirds have shown more complex mating systems, where multiple adults help raise a brood.

Where do bluebirds get their vivid color from?

Kincaid says that, unlike red or yellow birds, bluebirds get their showstopping blue color from a totally different source.

“The blue comes from melanin and how the feather structure reflects light, which is why they seem to glow in the sunlight,” she says.